Mar-Aug 1995 – Pumpkinland and Chicago Recording Company

Produced by Flood, Alan Moulder, and Billy Corgan

- Beautiful

- Beautiful (loop version)

- Bodies

- Bullet with Butterfly Wings

- By Starlight

- By Starlight (Flood rough mix)

- Cherry

- Cupid de Locke

- Farewell and Goodnight

- Farewell and Goodnight (rough)

- Fuck You

- Fuck You (rough mix)

- Galapogos

- God

- Here Is No Why

- In the Arms of Sleep

- In The Arms of Sleep (early live demo)

- Isolation

- Jellybelly

- Jellybelly (instrumental pit mix)

- Jupiter’s Lament (barbershop version)

- Knuckles

- Lily (My One and Only)

- Love

- Love (rough mix)

- Lover, Lover (acoustic demo)

- Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness

- Mellon Collie (Nighttime Version 1)

- Muzzle

- One and Two

- Porcelina of the Vast Oceans

- Porcelina of the Vast Oceans (rough mix)

- Set the Ray to Jerry

- Set The Ray To Jerry (vocal rough)

- Speed

- Star Song

- Take Me Down

- Take Me Down (instrumental)

- Tales of a Scorched Earth

- Tales of a Scorched Earth (pit mix)

- Thirty-Three

- Thru the Eyes of Ruby

- Thru The Eyes of Ruby (take 7)

- Thru The Eyes of Ruby (pit mix 3)

- Thru The Eyes of Ruby (acoustic)

- To Forgive

- Tonight, Tonight

- Tonight, Tonight (band only)

- Tonight, Tonight (strings only)

- Tonight, Tonight (acoustic inst)

- Tonite Reprise

- Tonite Reprise (Version 1)

- Tribute to Johnny

- Ugly

- We Only Come Out At Night

- Where Boys Fear To Tread

- XYU

- XYU (take 11)

- Zero

- Zero (synth mix)

- Zoom

- 1979

- Cupid de Locke (instrumental)

- In The Arms of Sheep [clip appears in Pastichio Medley]

- Envelope Woman (take 1)

- Envelope Woman (take 2) [clip appears in Pastichio Medley]

- Muzzle (rough vocal)

- One and Two (Billy vocal)

- The Tracer [clip appears in Pastichio Medley]

- Where Boys Fear To Tread (alternate take)

- XYU (take 1)

- XYU (take 2)

- A Dog's Prayer

- Feelium

- Keep It

- Methusela

- Mouths of Babes

- Phang

- Rock Me

- Spazmatazz

- Speed Racer

- Ugly (3 alternate versions)

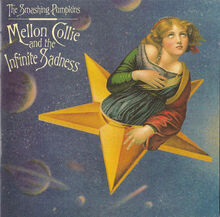

Massive recording sessions proper for the massive Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness album. Sessions initially began at the band's rehearsal space Pumpkinland, largely tracking the songs live. Sessions were later moved to Chicago Recording Company for further tracking and overdubs. Many songs were recorded, aside from the 28 album tracks: "Cherry", "God", "Set The Ray To Jerry", "Tonite Reprise", Tribute To Johnny" and "Ugly" were all released as b-sides; snippets of "Knuckles", "Speed", "Star Song" and "Zoom" all appeared in the Pasticio Medley. The full-length "In The Arms of Sheep", a rough vocal version of "Muzzle", "One and Two" with a Billy Corgan lead vocal, two takes of Envelope Woman, two takes of XYU, an instrumental Cupid de Locke, an alternate take of "Where Boys Fear To Tread" and a full-length "The Tracer" leaked as mp3s on the internet in 2010.

“People don’t always articulate their expectations,” says Corgan. “I think whenever we would work with producers, they would do their best to try and balance those forces between what somebody would want, what I would want, and what was best for the record.”

Before a single note was recorded, Corgan knew he wanted the next release to be a double album. Flood and Alan Moulder, friends since their early days at the prestigious Trident Studios in London, were tapped to co-produce. The band began rehearsing at Pumpkinland, their Chicago recording space, and Billy began funneling cassette demos to Flood for review. Roughly two-thirds of Mellon Collie & the Infinite Sadness was tracked at Pumpkinland on an Otari MTR-90 MKII, while the remaining portion was tracked at the Chicago Recording Company on Studer A820s.

“I love recording at 15 ips NAB, but with Dolby SR, because it just adds a whole different dimension to the sound,” says Flood. “Apart from the obvious benefits of Dolby, if you tweak the Dolby unit really, really well, it’s a bit like adding an Aphex and a dbx sub-harmonic bass enhancer on every channel. Also, the way that tape changes the sound or modifies the sound, 15 ips is technically not correct, but I find it to be so musical, particularly on the bottom end. This was very much a conscious decision, and very much a part of the album’s sound.”

Another conscious decision was to change up the manner in which the group recorded. In the past, the band had only used one room to track, which of course meant only one thing could be going on at a time. Hours spent waiting for one person to finish up their part led to frustration. For Mellon Collie, Flood would generally work with Corgan in the A room on the Otari and an MCI board, while Moulder worked with Wretzky and Iha in the B room on a Pro Tools rig slaved to both TASCAM DA-88 digital recorders and two-inch tape. The combination of analog and digital opened up a world of recording possibilities, and played to the creative strengths of Mellon Collie’s adventurous spirit. A track like “Thru The Eyes Of Ruby,” which contains approximately 70 guitar tracks, would have been nearly impossible to do with tape alone. Likewise, “Porcelina Of The Vast Oceans” contains roughly six sections that were all recorded at different times with different instrument and microphone configurations and then fused together—another beneficial byproduct of editing in Pro Tools.

Guitar and amplification choices were the key differences between Siamese and Mellon Collie. For the bass, Wretzky switched up from the P-Bass to a ’60s era Fender Jazz Bass reissue with Ampeg and Mesa Boogie amps. For Corgan, what sounded great about the Siamese fuzz pedal setup in the studio made it sound horrible live. He still had his Marshall 1960A cabinets, but Corgan shifted to a Mesa Boogie Strategy 500 and a Marshall JMP-1 preamp (Corgan also notes that he used an Alesis 3630 to drive extra gain into a Marshall). As the ultimate goal for Mellon Collie was to capture the band’s live, unbridled sound, Billy largely used this touring rig to record.

“Flood felt like the band he would see live wasn’t really captured on record,” says Corgan. “So a lot of Mellon Collie was tracked by the band at deafening volumes. I mean deafening. There was so much SPL in the room that it was physically uncomfortable. Your ears, your emotional resistance, would wear down.”

Flood also discovered that Corgan was a much better singer pitch-wise when he didn’t use headphones, so he switched Corgan up to a Shure SM58 and had him sing in front of open speakers.

“My experience with U2 taught me that a lot of things you’d expect to become problematic with monitors in the room aren’t, and by careful use of screening, by positioning the monitors and what you put in the monitors you can actually get a lot of benefits,” says Flood. “For instance, Jimmy used to love having the kick drum and a bit of snare going through his wedges, which were directly behind him. So if you’ve got a kit that’s lacking a bit of bottom end, you pump the kick and the snare through the wedges and you start to tweak them to get extra weight. We also developed this system whereby we had what was called ‘rehearsal mode’ and ‘tape mode.’ In rehearsal mode, everybody was on the floor, the amps were blaring, and you wouldn’t have to worry about spills. We had the speakers inside these big coffin flight cases in the back of the room and miked them close up, then miked them about six feet away. Then we’d close the lid. When you were tracking in tape mode, everybody could flick over at the flick of a footswitch and their amps would be quietly purring away in the corner. When you’d give a little bit back to them in their own respective monitors, automatically the sound of the room cut right back and you’d get the vibe of four people playing on top of each other.”

For the drums, Chamberlin’s core Mellon Collie kit was a Yamaha Maple Custom with a 16x22-inch kick, a 22-inch ride, 18-inch and 19-inch Zildjian A Custom crashes, 22-inch swish knockers, and 10-inch and 15-inch fast crashes. Because of his big band background, he frequently changed out his snares, building his kit around the snare and the ride as opposed to the kick. The familiar drum rolls all throughout “Tonight, Tonight” can be attributed to Jimmy’s classic 5 1/2x14- inch Ludwig Supra-Phonic.

“From there I go to microphones as far as how I want the drums to sit dimensionally in the track,” Chamberlin informs. “If I want the drums up front and aggressive, I’ll use a lot of AKG C 414s so they sit in front of things dimensionally. If I want the drums to sit in a rhythm section configuration, I’ll lean back towards the 414s and maybe some Shure SM98s. Then maybe go for Shure 12As on the bigger drums.”[1]

Having thrashed out the basics of the album in a month and a half at their own rehearsal facility in the band's native Chicago, the Pumpkins moved into a recording studio proper. Or rather, two of them. Moulder and Iha in one room, Flood and Corgan in the other, the days were crammed with constant dicking around with guitar sounds.

"The main difference between Siamese Dream was very methodically recorded: drums, bass, guitar, vocals, everything was overdubbed. But on this record everything varied from song to song. We did anything from overdub overload to-Thru the Eyes of Ruby has something like 25 separate guitar tracks-to actually recording all live at the same time as a band. The time in our practice space was well spent, cos we didn't have to feel self conscious and we didn't have the clock ticking over our heads we just got the band rocking!"

Although Iha wrote the music for two of Siamese Dream's most memorable tracks, Soma and Mayonaise ("I get my George Harrison allocation!"), the record seemed very much the work of one man. Corgan's perfectionism looms above everything, while the lyricist played 90m percent of the guitar solos. This time Corgan and Iha lead guitar split is closer to 50/50, and the whole record has a looser spontaneous ambiance. "I think that the fact that we had two rooms going gave us the scope to say whatever works, works, " muses Iha. "It was studied, but it was less perfectionistic. And we were less inclined to revert to a formula-like here's the Big muff pedal and let's triple track it. This time it was, Oh one guitar sounds okay let's go with that. I used the Digitech Whammy pedal a lot on the record, and I used an E-bow a lot too, which is something we haven't used for five years or something. Flood helped a lot. His thing is not going for the perfect take but the take that feels best. There was less technical obsessiveness and more feeling-which was totally refreshing. And the producers kept everyone busy. Flood would ask Jimmy (Chamberlin drums) to come in a little earlier, just so they could work on a bunch of drum loops before the rest of the band arrived. I'd go and check out D'arcy recording her bass and them later on I would just fuck around with the guitar. It was just "funner", and we ended up learning a lot of cockney slang and discovering Reeves and Mortimer."[2]

Billy Corgan: Flood, I felt, understood what I was trying to get at. My sense of it is Flood came to see us play live and said, "I want to record that band." Flood being Flood, would be way more attracted to the band as we really were, as opposed to the shiny version. He's more than capable of doing the shiny version, but I think he thought the other version was going to be a lot more fun.

Flood: When you watched them live, at that time, during Mellon Collie..., I don't think I've recorded a better band. They were so amazing, but it had to be all four of them there. They all needed each other in different ways. The groove and the feel of the combination of all of them; when they were really on it, nailed it, and knew what they were doing, it was amazing. Jimmy and Billy are so creative. Sometimes Jimmy might come up with guitar bits, or Billy might a have technical idea, so it was a really special time because no one was really overbearing ego-wise at all. As co-producers, Billy was one of those artists I've worked with who just had creativity coming out of every pore and he wanted to push; he never wanted to stagnate. He had ambition and he was always pushing. They'd rehearse a song until it felt right. You could say "genius," or you could just say somebody's found their calling and they're not frightened by it. They wanted to embrace it and push it as far as they possibly could.

Alan Moulder: Flood and I, as a team, both have the same sensibility about what we want from a record. We both want excitement and passion, so the same things get us excited. We work very well together that way, and we're free to argue without fear of anything being personal. We always know if we're arguing that it's a creative argument. We actually enjoy arguing, because it's more like you understand what the other person's hearing and it makes you hear the song in another way you might not have thought of. So we're free to say what we think without having to worry about each other's feelings, because we know nothing we say is meant to hurt that person's feelings. It's purely the creative war, if you like. It was the same way with Billy, making that record, and he would be an absolute fraud if he was not a co-producer. The team of the three of us was great, and a similar thing; where nothing was ever taken personally from what was said. We all felt everyone was confident in each other, and nobody knows how the Pumpkins should sound more than Billy. He was ahead of the charge, in terms of the vision and headspace where things came from.

Billy Corgan: When we played particularly difficult songs, like "Fuck You (An Ode to No One)," Flood would have us practice the song every day, first thing in. So we started every workday with an hour of band practice, and afterwards we would do two or three takes of "Fuck You," or whatever was the crazy, prog- gy, heavy song of that day. "Bullet with Butterfly Wings" is another song that comes to mind. So we would get in a really good, almost live, frame of mind. Then he would track it, and sometimes he would say, "Ehhh, wasn't very good. We'll do it again tomorrow." We would never get too stuck on anything.

Flood: With "Bullet...," really early on when we were going through all the demos, it was quite obvious that the great thing about working with the Pumpkins was that it was obvious which tracks were going to be the real main players. That was most definitely one of them, and we all knew it because it had the energy we wanted to capture.

Billy Corgan: Most producers usually get out of the way with me with guitars. They know that I'm a charging bull there. They don't have a whole lot to work to do with me on the guitar, so one could argue I've rarely been produced on the guitar. Vocally, however, I think I've benefited from working with great producers like Flood, who've gotten the best out of me as a vocalist. I probably haven't done as good a job when I've produced myself. That's probably the hardest thing to do, is to have a critical eye, because I don't know any singers who love their voice. I hear that all the time. It's really hard to hear your voice and hear it the way other people hear it. So, for instance, early on, Flood realized that recording me with headphones was not only a challenge for pitch, but it was taking away some of the nuances in the personality of my singing; which he wanted more of, not less. So he freed me up to sing with a handheld [Shure SM]58 and the speakers on full-blast in the control room. By doing so, he got the singer that he saw on stage. Obviously we wanted the best version of that.

Flood: "1979" had been running around for a long time, and it had started to turn into one of these songs that every album has – where you just grind, and grind, and grind away, and it just won't turn any other color except for gray. You spend all your time on that one song, and it usually doesn't make the album. So it got to almost the last day of recording at Pumpkinland [the band's rehearsal complex] before we were going to swap over into CRC [Chicago Recording Company], and I went, "Alright, that's it. You've got one more day." We'd spent a load of time going through the song again and it just wasn't happening, and I said, "One more day. That's all this song's got, and then I'm gonna chalk it. I'm gonna drown the child." And everybody was going, "No, you can't do that!" And I said, "I can. I'm so bored of it."

Billy Corgan: I still remember the fateful day, sometime during the last week in the studio, when Flood turned to me, looked at the song, and in a very professorial way said, "You've got 24 hours." Meaning, "If you do not come in here tomorrow and have that song figured out, it's off the record. We don't have time to fuck around with these things anymore. We need to focus on things that need attention, because they're gonna be on the record." So I went home. I don't remember working on it all night, other than when you listen to the demo, the demo sounds remarkably like the record. So much so that we even took the drum beat: the exact tempo and exact programming from that machine – and that became the foundational basis of where we started. Then Flood and I worked basically alone, throughout the day, and added little pieces of prog rock and little new wave punches. We built this painting of a track. There was no sense of rules or, "It's gotta be like this." There was no sense of even, "Does this fit on the record?" We just got really excited by the version that we were into. Everything you hear on the track – except for the vocals – is from that one 12-hour span. We built the track up with just the drum machine. But then it was like, "Should we have Jimmy play on it?" We had Jimmy go in, and I think he played for four minutes to a click; just played the same beat, over, and over, and over again. Then we took the one bar that I liked, put it in the Kurzweil K2600, fucked it up, laid it in the track, and were like, "Oh, that works!"

Billy Corgan: Then the famous "no one knows what I'm saying" thing at the beginning; I heard that in my head, picked up a 58, sang it into the Kurzweil, fucked that up, and looped it in. We thought, "We'll replace that later with a keyboard," because I heard it more as a melody idea, and then it just stuck. When we went to take it off, and they were like, "No, this is too good." It was like a beautiful day of weird stuff.

Alan Moulder: That's a classic Flood production: the vocal effects and the Kurzweil distortion on the drums. I think once they decided how to do it, it came together rather quickly. That was a special song.[3]

James Iha: I think Flood helped the band...to not repeat the way we recorded before. In comparison, the last record was a lot more produced, there's less of a live feel - I mean, it's really good, just more produced I suppose. The thing about the new record is that on a lot of songs we went for more of a live feel. Like on "Bullet"...it's a lot more stripped down than how we would've approached it before. I mean, there's a lot of guitars on there, but, they weren't done just for the sake of it, like we can overdub twenty-four guitars or whatever. It's just two rhythm guitars.

At some point there are one or two other guitars that come in...there's a lot of drop in sort of stuff. In the second verse there's this wah-wah sort of thing. It was just this mistake I made on the guitar and we ended up sampling it. We degraded the sound with distortion and I ended up playing it on the keyboard in time with the music. So there's neat things like that on the record. There's more space to do stuff like that because there isn't 24 rhythm guitars.

A lot of that is because we used a lot of Marshall amplifier distortion. It's a cleaner sound, but more powerful. It has a lot more "throw" to the sound. The fuzz pedals sound so washy, you can't tell what you're playing. You could just be fucking off and it would sound good. I think that's what a lot of bands do now. The Big Muff distortion pedals are like the DX-7 keyboard of the 90's - everybody uses it. It's like Nirvana, clean during the verse, step on it for the chorus. I mean, Nirvana were awesome, totally amazing rock band, but everyone's just stealing their formula. It's kinda lame.[4]

Billy Corgan: On much of the album, I used my old 1984 Marshall JCM 800 100-watt top, which is my favorite amp; it's on every Pumpkins record. I bought the amp with a 4x12 bottom-I don't even know what kind of speakers are in it-and used the bottom for most of the guitar tracks. My other main rig is the Marshall JMP-1 rack preamp, which goes into an Alesis compressor and then into a mesa is its "half amp" thing, which allows you to cut the wattage in half. That helps the way the sound hits the power section of the amp and gives it a certain kind of compression, which sounds really good. I like the amp's "presence" control, too. Power amps don't give you much in the way of controls a lot of the time. But I don't use the Mesa in stereo because I think stereo guitar sounds like shit.

"Jellybelly" is a good example of the Marshall rack and Alesis compressor guitar sound, which is the basic "fat" rhythm sound I use. I used the JCM 800 for most all of the overdubs on the record. That's the JCM at work it kicks in really heavy [at :23] during "Thru the Eyes of Ruby," That amp has a certain cut to it that sounds great. Because of the total differences between the two setups, I tend to use the JCM 800 more for leads, solos and overdubs than for rythem. Using two setups together makes the different guitar parts work better together-to "sit" better. On Siamese Dream I did everything with that JCM head, so it was harder to get tonal differences on each guitar part.

On "To Forgive," I used a Fender Bassman that I bought during the recording of Siamese Dream. It's an old, fucked-up amp, one of those "silver face" models from the late Sixties or early Seventies. I paid to get it fixed, but it still doesn't work right. The amp makes this weird sound, like a storm coming. While we rehearsed the song, the sound got worse, and then started to go away,at which point we started to record. Right about the time we did the rake that's on the album,the sound started to come back. If you listen closely, you can hear a little bit of the storm sound coming again. No, it's more like KKKkkkccchhhHHH, like something's definitely wrong with the amp. I've had problems with tubes going harmonic, but this is something else altogether. I've tried kicking that head as hard as I can, and sometimes that makes the sound go away. But other times it makes it get worse, so you have to know just when and how to kick it! [laughs]

I can pretty much get everything I want from my rack setup. James has a Fender Twin, which we used on some tracks for cleaner tones. Come to think of it, we did use a Vox AC-30 on a lot of tracks. It's a '64 that someone lent us, and it sounded fuckin' great. I used it on "Tonight, Tonight" and "By Starlight." At the very end of "By Starlight," there's a feedback and octave thing I do [beginning roughly at 4:12], and it's just me standing in front of the amp and cranking it up. I double-tracked it, so I'm getting different feedback on each track. It was difficult because I wasn't used to playing with "Vox" feedback. It was hard to get the guitar to feed back in the range I wanted. When I went back and double-tracked it, I went for feedback in a higher range, which created weird dissonance when I put the two tracks together. Also, when I used that amp, I mostly played a '72 Gibson 335 instead of my standard '57 reissue Strat.

When I recorded the rhythm guitar tracks to "Fuck You," it was the first time I tracked with the album's co-producer, Alan Moulder. Flood, whom I'd been tracking with, had left town. I recorded the first rythem track and did a little neck pull at the end. Then I did the other track without listening to the first track, which is how I always do guitar double tracking. At the end of the second track, I pulled the neck again and said to Alan, "Okay, watch this." The I played them both back, without the drums, and we listened for discrepancies. Alan absolutely could not believe I did the neck pull-out of time, no less-at exactly the same moment, It's kind of a tribute to Alan, really, 'cause I did it to freak him out. I've double-tracked for so long now that I know all of my little idiosyncrasies. I knew from the "feel" in my body when to do the pull.

I just took a driving trip, and listened to the whole album for the first time in a couple of months, and stuff jumped out at me that's hadn't before. Like "Tales of a Scorched Earth," which is just a bit about teenage nihilism. When I recorded the song, I had mixed feelings about putting it on the album, but when I just got away from the intellectualizing and just listened to it, I enjoyed it. It's total bombast. Within the context of the whole record, it fits nicely. It's a nice opposing ice cream flavor. I overdubbed an unusually tuned guitar part on the chorus. The G string goes up one half step to G# and the high E strings goes up one whole step to F# [all pitches actually sound on half step lower, as all the guitars are tuned down one half step]. Then the guitar is run through a kind of envelope filter, so it sounds strange. There's a lot of different things going on during the bridge: there's a regular bass, there's a Fender P-bass played with a pick [playing a different line and sounding like a six-string bass], there's a few guitars played through envelopes, and there's a real scratchy guitar, too. There are about six or seven different instruments happening in there.[5]

Using computer technology, it seems that Corgan and Iha have confronted their post-guitar challenge. For Mellon Collie, the band employed Studio Vision Pro with Pro Tools running on a Macintosh 8100 to do loop samples and manipulate basic tracks. The techno-rig has potential: the Pro Tools application an handle up to 128 tracks. But because Corgan didn't learn about the technology until midway through the recording process, he and Iha applied their newly learned techniques only during post-production. For all their previous work on the album, the band used a 24-track analog machine and an additional 16 tracks on Pro Tools. (The new setup will likely be used to its full advantage on their next project.)

Commenting on his initial exposure to the digital technology, Corgan says, "At first it was like, 'What a bunch of f*****' dry s***.' But once you learn it, you stop thinking about it. I really feel I can finally go in a field where no one's been." Iha feels the same. "I think it's a great tool. There's a big misconception about samplers. You don't have to use it like Nine Inch Nails to make an impact. It should be just like using a different guitar pedal."

Corgan explains that the track "Keep It" on the new record is a good example of the way his new machines have provided him with a different recording technique. "We recorded the rhythm-section part of the song first then I had Jimmy & D'Arcy [bass] play the bridge for a few minutes.

Later, I'd go back and find the best two to four bars of the bridge, sample it, and run it through the song. We did that for each section of 'Keep It,' and then I assembled them--the rhythm section and the guitar loops--then I manipulated the sounds by running them through high-pass filters. Suddenly you have something that doesn't sound like anything you've done before." Corgan's eyes light up with the thought of having a new and infinite spectrum of creative possibilities. If it wasn't clear on earlier records like Gish and Siamese Dream, it's obvious now that he thrives on new ideas.

Newfound admiration for technology aside, Corgan and Iha used their traditional setup when laying down most of the basic tracks for Mellon Collie. Corgan played predominantly through his super-tweaked live setup: an Alesis compressor, a Marshall rack preamp and a Mesa/Boogie 500 Series power amp. For pedals, Iha and Corgan layered it on thick: Big Muff Fuzz, Fender Blender, a DigiTech Whammy, Eventide harmonizers, wah--you name it. They sometimes laid down 8 or 10 guitar tracks at a stretch. For their guitars of choice, the simple formula remained as it has since the beginning: Strats and Les Pauls.[6]

Billy Corgan on "Bullet with Butterfly Wings": Believe it or not, the original riff from this song came to me during one of the Siamese Dream recording sessions. Somewhere, I have a tape of us from 1993 endlessly playing the "world is a vampire" part over and over. But it wasn't until a year and a half later that I finished the song, writing the "rat in the cage" part on an acoustic guitar at the BBC studios in London on the same day that "Landslide" was recorded.

Billy Corgan on "Cherry": Of all the B-sides, this song is probably my biggest regret. I never spent as much time on it as it probably deserved, with this version showing very little improvement from the demo. This one probably should have made the album. I love its feeling and atmosphere, the warbly guitar courtesy of an effect that changes oscillation in ratio to signal input (the harder you hit it, the faster it goes). The basic tracks were recorder during the Mellon Collie sessions.

Billy Corgan on "God": Forever slated as a Mellon Collie song-to-be "God" just couldn't cut it in the end. The beat was probably a little to close to "Bullet," but it still rocks hard. It was tracked during the Mellon Collie sessions, with overdubs and vocals added much later.

Billy Corgan on "1979": The most frequently asked question about "1979" is, "What is the 'ooh-ahh-ahh' sound at the end of every phrase?" Flood and I were tracking the song, and I started humming the "oohs" like a melody line. I sang them to tape, we sampled the pertinent ones, electronically manipulated them, and looped them against the drum beat. One of my favorite songs from the album.

Billy Corgan on "Set the Ray to Jerry": Another remnant of a distant Siamese Dream past, "Set the Ray to Jerry" was first written somewhere during the Gish tour. It's always been a band favorite, and seemingly only the band's, because no one ever mentions it. A sweet, simple song featuring only bass, drums, and some delayed James guitar. One night Flood and I put everything we had on a couple of tapes (about 40 songs) and just drove around Chicago until 3:30 in the morning deciding what was on or off the album. When we listened to "Set the Ray," it really moved me, but when I looked over to Flood he just shook his head no. That was the end of "Set the Ray" on the album, because I trust Flood's opinion so much.

Billy Corgan on "Thirty-Three": A simple song in a country tuning, "Thirty-Three" was the first song the I wrote when I came home from all the Siamese Dream touring. I took three days off, and this was literally the first thing that came out of my hands when I sat down. I was living in my new house for the first time, and this song conveys all of that. The "cha-cha-cha" sound is my drum machine through a flanger, and what you hear is the same one right off the demo because I couldn't remember how to recreate it. The stringly sounds are part Vocoder, plus five slide guitars tuned to one note each to create the chords.

Billy Corgan on "Tonite Reprise": Originally slated to go on towards the end of the Mellon Collie album, this one was hacked off in the name of "When is enough too much?" I had just come back from the Chicago Bulls' tragic loss to the Orlando Magic in the playoffs [May 18th, 1995], and was very depressed. My voice was hoarse from so much shouting. Flood threw up his famous mikes, and I just did it live. I used my trusty Gibson acoustic, with the rusty strings.

Billy Corgan on "Tribute to Johnny": Our tribute to Johnny Winter, circa 1974; a true original, and one of my favorite guitarists.

Billy Corgan on "Ugly": Started as an album song until the very last moment, when Mellon Collies\ was cut from 31 to 28 songs, this is an interesting interpretation of what had essentially been an acoustic song. Flood and I tried about four different versions before settling on this one [see Queen's Hot Space album]. One version that I liked was just me and a distorted guitar. But in the end this version won, only to be mixed into eternal obscurity as a B-side.

Billy Corgan on "Zero": We like to call this style of our music "Cybermetal." "Zero" has six rhythm guitars, with two line-in 12-string acoustics, plus those wacky Iha leads. Tracked live with overdubs added later, this is a true mover as well as the first song that was recorded for Mellon Collie, James has always said this reminds him of Judas Priest.[7]

Return to Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness

- ↑ Richard Thomas, "Signal To Noise: The Sonic Diary Of The Smashing Pumpkins", Electronic Musician, October 1st, 2008

- ↑ Danny Eccleston, "Gourd Vibrations", TGM Magazine, December 1995

- ↑ Jake Brown, "Smashing Pumpkins: A Studio History", Tape-Op, Sept/Oct 2016

- ↑ James Iha, Interview with Paul Bernstein, September 1995

- ↑ "Orange Crunch", Guitar School, April 1996

- ↑ "No More Guitars", Big O, 1995

- ↑ Billy Corgan, "King Bs", Guitar World, January 1997